/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/34171283/183645792.0.jpg)

A big part of the American Dream is being able to climb the ladder and land higher than your parents. But that climb starts when people are just small children, according to new research, and getting off on the wrong foot has lifelong consequences.

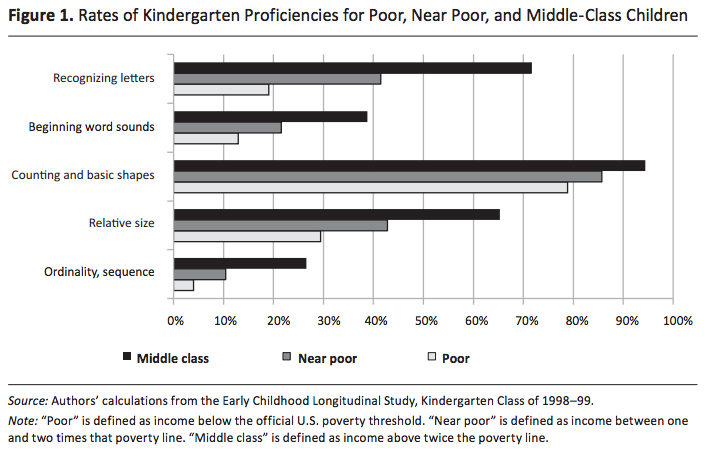

In a new article in the spring issue of the Princeton University journal The Future of Children (and highlighted by the Brookings social mobility blog), researchers show that poverty is directly correlated to kindergarten performance. Children who live in poverty have far lower performance than their richer peers across a variety of measures, and those who live in near poverty in turn have dramatically worse performance than middle-class peers. The poorest kids, for example, are less than one-third as likely as middle-class kids to recognize letters.

Research has shown that an early head start creates better and better educational outcomes down the road, as the effects build on each other and make future learning easier.

The authors dig into the effects of income on achievement, finding that "adults who were poor as children completed two fewer years of schooling and, by the time they reached their 30s, earned less than half as much, worked far fewer hours per year, received more in food stamps, and were nearly three times as likely to report poor overall health" than their peers whose families earned at twice the poverty line or more (though the causal linkages on health don't appear as strong as those on later achievement).

Early academic achievement can have lifelong effects. Harvard economist Raj Chetty found in a 2010 study that moving from an average to an excellent kindergarten teacher can boost a student's later work earnings by $1,000 per year on average. And Chetty and fellow economists from Harvard and Berkeley wrote in a wide-ranging study on economic mobility this year that primary education is one of the key factors in moving people up the ladder.

It's not that money directly buys better outcomes. Having extra cash does mean that adults can, for example, better invest in kids' development with games and toys at young ages and have more time to spend with kids. But the effects are also less direct, as growing up poor can create psychological stress and hurt development.

All of which is to say that there a couple of important lessons here about economic mobility. One is that policywise, investing in things like the Earned Income Tax Credit and early childhood education could be instrumental in helping poor kids up the ladder.

More importantly, this means boosting economic mobility is likely to be a long, complicated fight. Even if there were jobs right now for everyone who needed them, the lingering effects of poverty would still limit some people's abilities to earn. And making sure today's children don't go through the same cycle means policies that touch not only on job creation but education.